Deadly Force

Cannoneers of the Confederate Washington

Artillery

Undaunted

Valor- A Dedication to Duty

"Artillery Duel"- Washington Artillery

cannoneers in action

(click on image to become part of crew &

receive orders to fire cannon!)

The Washington

Artillery’s reputation of valor, honor, and deadly accuracy during the War

Between the States soon spread though

the North and South. It was not a disgrace to fall to the mercy of their deadly

fire. Its name was written in numerous newspapers and given laurels in many

battle reports. A good example of this fame was documented following the battle

of Drewry’s Bluff when a Yankee prisoner, Captain Belger, asked as he passed the

artillery unit, “What battery was that, that I was fighting?” One of its members

responded, “First Company, Washington Artillery.” The Captain’s expression then

changed, and he replied, “Damn that Washington Artillery! I have been looking

for it for three years and have found it at last.”

The art of

muzzle-loading artillery reached its lethal zenith during the Civil War. Its use

as support during an infantry attack, or repulsion of a frontal enemy attack

could serve as a great “equalizer.” Private Stephenson of 5th Company bragged

about his unit’s cannons. “Our guns were 12 pound brass Napoleons, smooth bore,

but accounted the best gun for all round field service then made. They fired

solid shot, shell, grape and canister, and were accurate at a mile. We would not

have exchanged them for Parrot [sic] Rifles, or any other style of guns. They

were beautiful, perfectly plain, tapering gracefully from muzzle to “reinforce”

or “butt,” without rings, ridges, or ornaments of any kind. We are proud of them

and felt towards them almost as if they were human, although for that matter our

attachment suffered the pangs of all attachments in this world, viz: of short

life and separation.”

However, Confederate

artillery units’ accuracy, including the Washington Artillery, was severely

limited by the Confederacy’s poorly manufactured ordinance. This limitation was

keenly observed early in the war by then Lieutenant T. L. Rosser of Second

Company in his battle report after Manassas. “The inefficiency of the case and

shell projectiles furnished me for service of the rifled guns was again

exemplified in this engagement, not one of them exploding. The “Boarman” fuze

[sic], with which the spherical case and shell for the howitzer were served,

showed, in their manufacture, great deficiency. There was no uniformity

whatever in their burning. Some cut for five seconds did not burn, in many

cases. Two others cut at two, burnt as long as four or five seconds.”

The Washington

Artillery, like all other Civil War artillery units, fought with muzzle-loading

cannon. The cannon were either smooth bored or rifled, the latter having greater

accuracy. (Only one breech-loader, the Whitworth from England, was used by the

Confederates with success. However, this type of gun, though very accurate and

dependable, was used on a limited basis due to availability and cost.)

To fire a

“muzzle-loader” a bag of black powder was inserted into the muzzle, which was

followed by the shot, either solid or shell. Both were rammed down. Then a metal

“pick” was thrust into the rear of the barrel through the “vent,” ripping a hole

into the bag of powder. A “friction primer” was then inserted into the top of

the vent and attached to a long string with handle called a “lanyard.” The

lanyard was pulled, its friction causing an explosion within the primer and

sending the fiery charge down into the larger bag lying in the rear of the

barrel. The explosion of this powder bag inside the cannon propelled the shot

out forward through the muzzle. The barrel was then cleared of debris with the

“worm” and swabbed with the “sponge.” The process was repeated over and over

with deadly precision. A good crew could fire three times a minute. In a fierce

battle the safety steps of “worming” and “sponging” were often skipped with

occasional deadly accidents to the operating crew.

Artillery drill,

though boring, was needed. As cannoneers were injured or killed during battle,

substitutions were required to the various positions. All men needed to know how

to perform the duties of all cannon positions. Endurance was required as

witnessed by Frank Labrano of First Company at the Battle of Sharpsburg

September 17,1862. “Fighting commenced at daylight. We went in at 7 AM and

continued fighting until dark. Our Compy. [sic] repulsed 3 charges of the enemy

besides fighting 40 pieces of artillery. On the 4th charge we gave

out of ammunition we went after more, and came back. We held our ground. The

loss of the 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Cos. amounted to 39

killed & wounded. I [had] rammed 253 shots in succession.”

“With his last breath

whispering into Slocomb’s ear, ‘Captain, haven’t I done my

duty?’

W. W. “Billy” Sewell killed at Dallas, Georgia May 28, 1862

The men of

the Washington Artillery often witnessed scenes too gruesome to recount.

However, many tried; probably to show the horrors of war, probably to document

the tribulations of their fellow comrades. Either way, these accounts, though

graphic, served their purpose well. They often had a common theme. When called

upon to give that dreaded last full measure, a soldier’s final thoughts were

often of religion, loved ones or dedication to duty- sometimes giving oral last

wills and testaments. No wonder why the men often found themselves in song; if

they hadn’t, they might have all gone insane.

House at

Mayre's Heights, Fredericksburg near where WA was entrenched

Mayre’s

Heights, Fredericksburg, Va., December 13, 1863

During

the hottest time of this engagement the Twenty-fifth North Carolina volunteers

reached the hill where Captain Miller’s Third Company of Washington Artillery

guns were planted and poured volleys into the lines of the advancing enemy;

then, dashing down the hill to the sunken road, stood shoulder to shoulder with

[Major Robert] Cobb’s brave Georgians. In passing through Miller’s guns, their

fallen bodies had to be dragged from our muzzles before they could be fired. Corporal

[Francis Dunbar] Ruggles had picked up a blanket which one of them had dropped

in Squire’s redoubt, saying, ‘Boys, this will be a good thing to have tonight.’

A few moments afterward with his sleeves rolled up and his youthful figure all

aglow with the excitement, holding his sponge-staff in his hand ready to ram the

cartridge home, he threw up his hands and fell backward, killed. … When the

gallant Ruggles is killed, [W.F.] Perry springs forward and seizes the

sponge-staff as it falls from poor Ruggles’ hands, but in an instant he is

disabled by a shot through the arm which drops helplessly to his side. [J.E.]

Rodd, who has been holding vent has his elbow shattered. [C.A.] Everett takes

his place and he also goes down disabled. He is laid in the corner of the

redoubt with Ruggles’ lifeless body, but fearless to the last, calls to the boys

to let him do something; ‘cut fuse if nothing else.’ Now [C.A.] Falconer, who

was passing back of the gun, is shot behind the ear, and falls a corpse. Poor

Ruggles- he used the blanket that night, but as a burial shroud.

Henry Baker, First

Company, WA

His

Legacy

This cdv shows

Charles A. Falconer, Jr. with “Aunt Mary,” his servant.

Charles’

father died performing his duty at Fredericksburg, Virginia in 1863.

Dallas,

Georgia, May 27, 1864

T’

was here, at Dallas, that Tom B. Winston was killed. An awful shriek rang out into

the air! Shall I ever forget it? It pierced high above the dreadful din. ‘Oh-h-h

Christ Almighty!’ That is what the voice said. Voice of anguish in tones that

froze the blood. It was Tom Winston. His legs were torn off just below the

waist. As we went on fighting, a hasty backward glance saw him borne away on a

stretcher, his face and mangled form covered, a shapeless, shrouded heap. Not

dead, but fatally hit. He died that night. One of the saddest deaths at

Jonesboro was Louie Vincent. Not over seventeen- a short, thick set, fair haired

boy from New York. Gentle, good natured, faithful for duty. Our works were in a

miserable state … We were exposed enough as it was, and men were being hit. …

The ceaseless din of firing went on all about us- the ping, pang, thud, and hiss

of the sharpshooters’ bullets. It was a desperate plight. Something must be

done. … Louie sprang up, spade in hand. I do not think he had thrown but one

spade full of dirt, when he was struck. … ‘I am killed,’ he cried. [Felix]

Arroyo laid him gently down on his side in the trench, the blood gushing in

torrents from the mouth. Only one word more, escaped his lips, ‘Mother!’ That

mother, alas, was far away and could not help. May it not have been that the

very best help a mother can give her boy, she had already given, in prayer and

instruction and loving Christian example, laying him at Jesus’ feet, I cannot

say.

Philip Stephenson, Fifth

Company, WA

Felix

Arroyo

who

comforted the young dying Tom Winston.

The 5th

Company had two Arroyos in the unit at the time of the battle of Fredericksburg,

Charles and Felix.

Then there

were always thoughts of disgrace and how one might act in battle. Confederate

units, as Union, were often composed of friends, relatives, or fellow partisans.

This gave cohesion to the unit and reduced chances of cowardice among its

members.

How

great a misfortune a soldier considers it to be, to be disgraced in battle, and

what dejection and downcast looks settle upon his face where the reputation of

his regiment has in any degree been tarnished…A company or regiment that once

showed signs of weakness, makes its own soldiers ten times more distrustful of

each other’s valor in the next engagement, and unless the demoralization has

been cured, and confidence restored, is a source of danger rather than of

strength to an army, and will inevitably damn the reputation of any good men who

happen to be connected with it.

Napier Bartlett, Third

Company, WA

Pine

Mountain, Georgia, June 14, 1864-

One such

example was “a Frenchman of 5th Company named Barrail [sic, Pvt. A.

Barriel]. He was a Parisan [sic], proscribed by Louis Napoleon for the part he

had taken in the last uprising against him. His body was covered with scars; it

is said received in France. He was of middle age and stature, stout and

soldierly, of stern countenance and temper, taciturn, unsociable but faithful,

fearless, reliable, a valuable man. … Yet this man became a coward. Comrades

noticed it, but nothing was said. The change in him grew as dangers multiplied,

until, at Dallas, he showed manifest fear and a comrade had to take his place at

the gun. He then, at the first opportunity, crept back to the caissons in a

sheltered spot. …Our officers were indulgent and let him alone. … He was never

seen at the front, where the guns were. The man was completely cowed.

When the

shades of evening closed in around us that day on Pine Mountain, and the enemy’s

‘dogs of war’ were finally muzzled, the usual inquiry ran along the line, ‘Is

anybody hurt?’ No one at the guns. But word comes from the rear, that one is

killed there. And behold that one is Barrail! Back in that sheltered

little depression, almost like a cave where the wagons and caissons were parked,

Death searched him out and found him – leaning over a fire, frying pan in hand,

preparing his supper. One of the last shells burst in his face and scattered his

brains amid his supper in the pan! Death seemed to send the whisper it his heart

beforehand, ‘I am coming.’

Philip Stephenson, Fifth

Company, WA

Peach Tree

Creek at the edge of Atlanta, July 20, 1864

Oscar Legare,

age 17, but full developed, a magnificent specimen of a man, 6 feet or more, was

corporal of piece 3. As fearless a spirit as ever lived. He chafed at our defeat

and at our silence under the enemy’s fire. Springing to his gun, he called his

men to action. He was just in the act of sighting the gun, stooping behind the

reinforce, when a parrott shell struck the gun at the swell or reinforce,

disabled it, exploded and emptied itself and its contents full into the face,

head, and upper body of Oscar. … torn to pieces from the waist up. We found long

strips of flesh high up on the trees behind them.

Philip Stephenson, Fifth

Company, WA

Arthur

Fremantle, British observer of the war, recalled viewing the dedication of one

of the Southern artillerists of General Polk’s corps,

“I myself remember a

fine-looking man who had both his hands blown off at the wrists by unskilful

[sic] artillery-practice in one of the early battles. A currycomb and brush were

fitted into his stumps, and he was engaged in grooming artillery horses with

considerable skill. This man was called a hostler; and as the war drags on, the

number of these handless hostlers will increase.”

It must have

been a constant mental battle to see fallen comrades, dead, wounded and dying,

along the roadside. Often the question was asked, “Why him and not me?” Such was

the case of Napier Bartlett who documented his thoughts while passing fellow

Confederates at Gettysburg prior to his participation there the following day.

Gettysburg,

Pennsylvania, July 2, 1863

It was

not a particularly pleasant business any way to be worn out with marching and

then to be forced to mediate upon your chances for the morrow’s battle.

Especially as I can remember was the case at Gettysburg, when the dead and dying

of the two days preceding fights are lying on every side of you. You are

compelled to witness every stage of the death- from the unhappy victim

trembling with the last shiver of dissolution, to that of the corpse who sits

upright with staring eyes, or whose stiffened arm seems to point you yourself

the road to perdition on the morrow.

Napier Bartlett, Third

Company, WA

Thomas E. Williams was

one of those members of the Washington Artillery wounded during the July 3rd

Gettysburg artillery duel. He recovered from his wounds in time to take part in

the defense of Petersburg, Virginia in 1864. By then he was a seasoned veteran

and knew about the hazards of warfare, both emotionally and physically. On

February 13, 1864 this single, poor, and humble soldier wrote this emotional

last will and testament while awaiting his fate in the trenches of that town.

Thomas E. Williams

Eternal and Ever Blessed

God,

I desire to present myself

before you with the deepest humiliation of soul. … I come acknowledging myself

to have a great offending weight upon my breast and say with the humble

proclamation ‘God be merciful to me, a sinner.’ … This day do I, with the utmost

solemnity, surrender myself to thee. I denounce all former evils that have

dominated over me. I consecrate to thee all that I am & all that I have: the

faculties of my mind, the members of my body, my worldly possessions, my time,

and my influence over others, to be all used entirely for thy glory. … And when the hour of death

comes, may I remember thy Covenant, well ordered in all things and sure,

as my Salvation, though every hope and desire is perishing. …

Amen, T. E. Williams Petersburg,

Virginia

Williams’ will was not

needed at Petersburg. He survived the siege and went on to fight during the

battalion’s retreat to Appomattox. His devotion to his company and the Southern

cause led him to refuse surrender with General Lee’s troops there and fled with

many of his fellow members “into the mountains.” He finally surrendered and was

paroled almost a month later in Charlotte, North Carolina on May 5, 1865.

Like the

stress placed on Thomas Williams at Petersburg, the toll of war mounted upon the

minds of many a soldier. But not all had the fortitude to continue fighting and

killing. The following letter was written by John M. Colby, who served in both

the Louisiana Confederate navy as a member of the Crescent Artillery Company A

and the Confederate army as a member of New Orleans’ Crescent Regiment, to his

distant aunt living in the north. Colby, a relative of several Washington

Artillery members, was “burned out” with war and returned home to New Orleans to

take the oath of allegiance to the United States.

New Orleans, October 11, 1863

My Dear Aunt,

I have been

in the Army and Navy of the Confederacy, have been taken prisoner twice and

finally come home a sadder, if not a wiser man. I was married here in 1856 at

the age of 19, lost my only dear child in 58 and wife in 60. Thrown upon the

world with such early dissapointment [sic] and with no attachments it was no

wonder that I should throw all my energies into a cause that has caused the

death of many a better, better man than myself. The horror of Civil Warfare

experienced in two short years have brought me over to the Peace Society and God

grants the time is not far distant when this unholy, unnatural war will be

finished. I have three cousins in the famous Washington Artillery and much of my

schoolmates and associates are either in the rebel service, killed, or like

myself, tired of soldiering. You, who have at home amid plenty, know not the

horrors of this war. I hope … that peace is not far off and our great country is

once more restored to dignity and Union for “United We Stand” against the whole

world; for this nation is now like France was under Napolean [sic], as a nation

of soldiers, not citizens.

Despite these differences

of opinion between Confederate soldiers about the need for the continuation of

war, members of the Washington Artillery, like many other Confederate soldiers,

managed to maintain their sense of dignity and honor, despite their surrounding

world of destruction and horror. Henry Baker may have reflected the thoughts of

many Confederate veterans after the war when he said, “I try to forget all the

horrible acts of cruelty inflicted upon the Southern people at that time. Yet, I

never felt any resentment against the Union soldiers; they, like myself, were

fighting for a principle that was dear to their hearts, they to preserve the

Union, and we to protect our homes and the rights guaranteed us by the

Constitution.” He remembered one such episode that proved his point. “Our

battery was changing its position one day during a hot skirmish. I darted

through a piece of woods and ran upon a desperately wounded Yankee soldier. He

was startled when he saw me, and begged me not to kill him. I took off my

canteen of water and handed it to him. ‘Do you suppose.’ I said, ‘that the

Confederate soldiers kill their wounded enemy?’”

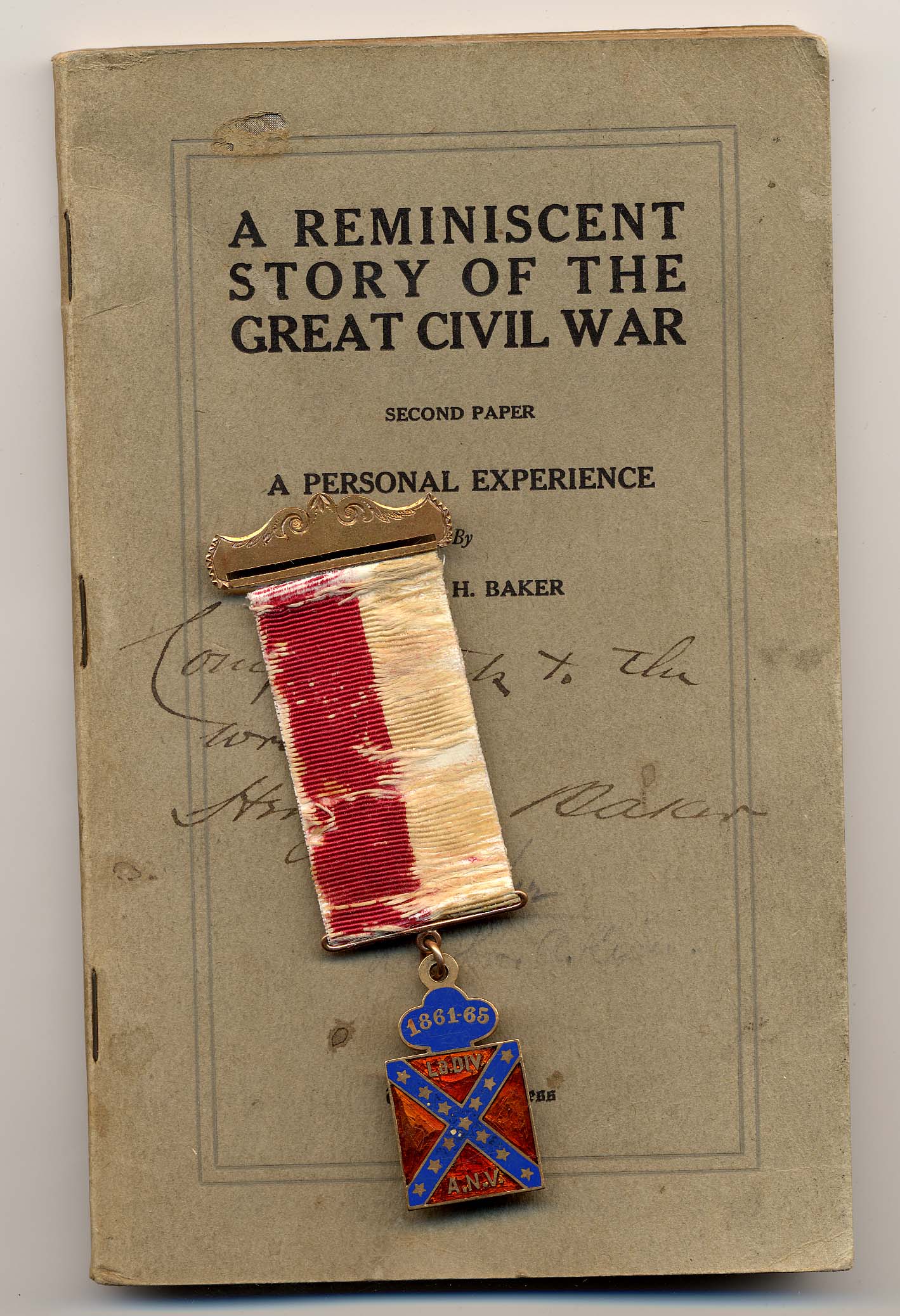

UCV medal and

book written by Henry H. Baker

HOME